Here is something all who want to learn about Common Core need to understand:

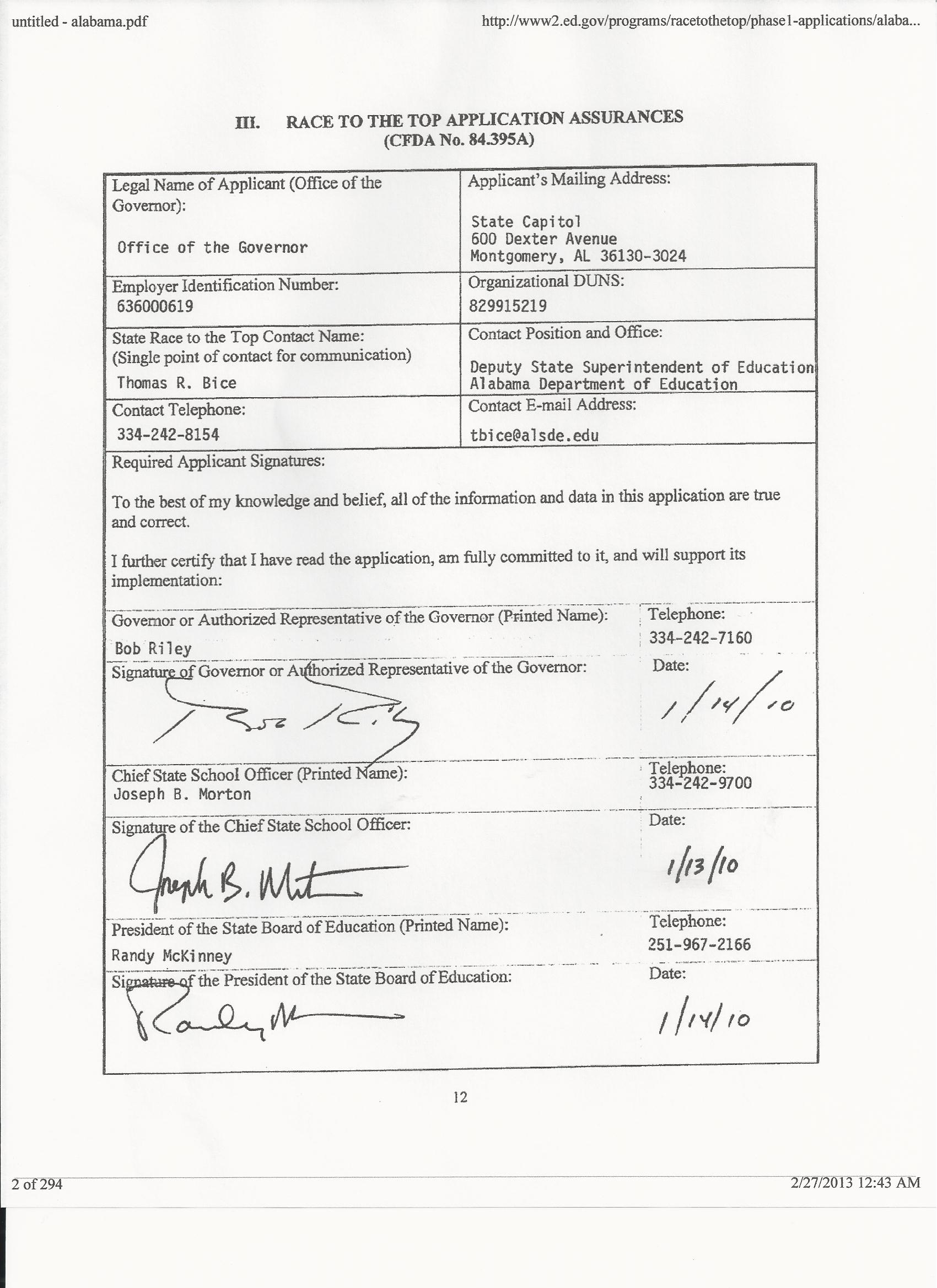

Look at the picture of when states governors signed on to the Common Core --it is on the Race To The Top Application--most did it in January 2010.

Then read excerpts from Professor Sandra Stotsky who tells you the behind scenes story of how each state's standards (ones that signed on to CC) were given up for the Common Core Standards while the standards were not yet finished. This was done to the children. All that mantra of rigor, bench-marked and tested must be understood for what it is. Come find out for yourself--here's one state (Alabama) example--study the picture with the letter from Professor Stotsky:

Common Core’s Invalid Validation Committee

Common Core’s Invalid Validation Committee

Sandra Stotsky

Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas

Paper given at a conference at

University of Notre Dame

September 9, 2013

Common Core’s K-12 standards, it is regularly claimed, emerged from a state-led process in which

experts and educators were well represented. But the people who wrote the standards did not represent the

relevant stakeholders. Nor were they qualified to draft standards intended to “transform instruction for

every child.” And the Validation Committee (VC) that was created to put the seal of approval on the

drafters’ work was useless if not misleading, both in its membership and in the procedures they had to

follow.

I served as the English language arts (ELA) standards expert on Common Core’s Validation Committee

(2009-2010) and in this essay describe some of the deficiencies in its make-up, procedures, and outcome.

The lack of an authentic validation of Common Core’s so-called college-readiness standards (i.e., by a

committee consisting largely of discipline-based higher education experts who teach undergraduate

mathematics or English/humanities courses) before state boards of education voted to adopt these

standards suggests their votes had no legal basis. In this paper, I set forth a case for declaring the votes by

state boards of education to adopt either set of Common Core’s standards null and void—and any tests

based on them.

For many months after the Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI) was launched in early 2009,

the identities of the people drafting the “college- and career-readiness standards” were unknown to the

public. CCSSI eventually (in July 2009) revealed the names of the 29 members of the “Standards

Development Work Group” (designated as developing the two sets of “college-and career-readiness

standards) in response to complaints from parents and others about the CCSSI’s lack of transparency.

About half of the members were on the Mathematics Work Group, the other half were on the ELA Work

Group.

What did the ELA Work Group look like? Its make-up was quite astonishing: It included no English

professors or high-school English teachers. How could legitimate ELA standards be created without the

very two groups of educators who know the most about what students should and could be learning in

secondary English/reading classes?

CCSSI also released in July 2009 the names of individuals in a larger “Feedback Group.” This group

included one English professor and one high-school English teacher. But it was made clear that these

people would have only an advisory role – final decisions would be made for ELA by the Englishteacher-

bereft ELA Work Group. Indeed, Feedback Group members’ suggestions were frequently

ignored, according to the one English professor on this group, without explanation. Because both Work

Groups labored in secret, without open meetings, sunshine-law minutes of meetings, or accessible public

comment, their reasons for making the decisions they did are lost to history.

2

The two lead writers for the grade-level ELA standards were David Coleman and Susan Pimentel, neither

of whom had experience teaching English either in K-12 or at the college level. Nor had either of them

ever published serious work on K-12 curriculum and instruction. Neither had a reputation for scholarship

or research; they were virtually unknown to the field of English language arts. But they had been chosen

to transform ELA education in the U.S. Who recommended them and why, we still do not know.

Interestingly, no one in the media commented on their lack of credentials for the task they had been

assigned. Indeed, no one in the media showed the slightest interest in the qualifications of the standards

writers.

In theory, the Validation Committee should have been the fail-safe mechanism for the standards. The VC

consisted of about 29 members during 2009-2010. Some were ex officio, others were recommended by

the governor or commissioner of education of an individual state. No more is known officially about the

rationale for the individuals chosen for the VC. Tellingly, the VC contained almost no experts on ELA

standards; most were education professors and associated with testing companies, from here and abroad.

There was only one mathematician on the VC—R. James Milgram (there were several mathematics

educators—people with doctorates in mathematics education and/or appointments in an education

school). I was the only nationally recognized expert on English language arts standards by virtue of my

work in Massachusetts and for Achieve, Inc.’s American Diploma Project high school exit standards for

ELA and subsequent backmapped standards for earlier grade levels. There were no high school English

teachers on the VC until one was appointed in late fall in response to my complaints.

As a condition of membership, all VC members had to agree to 10 conditions, among which were the

following:

Ownership of the Common Core State Standards, including all drafts, copies, reviews, comments, and nonfinal

versions (collectively, Common Core State Standards), shall reside solely and exclusively with the

Council of Chief State School Officers (“CCSSO”) and the National Governors Association Center for Best

Practices (“NGA Center”).

I agree to maintain the deliberations, discussions, and work of the Validation Committee, including the

content of any draft or final documents, on a strictly confidential basis and shall not disclose or

communicate any information related to the same, including in summary form, except within the

membership of the Validation Committee and to CCSSO and the NGA Center.

As can be seen in the second condition listed above, members of the VC could never, then or in the

future, indicate whether or not the VC discussed the meaning of college readiness or had any

recommendations to offer on the matter. The charge to the VC spelled out in the summer of 2009, before

the grade-level mathematics standards were developed, was as follows:

1. Review the process used to develop the college- and career-readiness standards and recommend

improvements in that process. These recommendations will be used to inform the K-12 development

process.

2. Validate the sufficiency of the evidence supporting each college- and career-readiness standard. Each

member is asked to determine whether each standard has sufficient evidence to warrant its inclusion.

3

3. Add any standard that is not now included in the common core state standards that they feel should be

included and provide the following evidence to support its inclusion: 1) evidence that the standard is

essential to college and career success; and 2) evidence that the standard is internationally comparable.”

It quickly became clear that the VC existed as window-dressing—to rubber-stamp, not improve, whatever

standards were declared as college-and career-readiness and grade-level standards. As all members of the

VC were requested to do, I wrote up a detailed critique of the draft college and career readiness standards

in English language arts in September 2009 and critiques of draft grade-level standards as they were made

available in subsequent months. I sent my comments to the three lead standards writers designated at the

time,1 as well as to Common Core’s staff, to other members of the VC (until the VC was directed by the

staff to send comments only to them for distribution), and to Commissioner Chester and the members of

the Massachusetts Board of Education (as a fellow member). At no time did I receive queries, never mind

replies to my comments from the CCSSI staff, the standards writers, or Commissioner Chester and fellow

board members.

In a private conversation at the end of November, 2009, I was asked by Chris Minnich, a CCSSI staff

member at the time, if I would be willing to work on the standards during December with Susan Pimentel.

We had worked together under contract with StandardsWork on the 2008 Texas English language arts

standards and, earlier, on other standards projects. I agreed to spend about two weeks in Washington, DC

working on the ELA standards pro bono with Susan after being assured that she was the decision-making

ELA standards writer. I then called Susan to discuss the kind of changes I thought the November 2009

draft needed before we began to work together and to clarify that agreed-upon revisions would not be

changed by unknown others before going out for comment to other members of the VC and, eventually,

the public. I then sent an e-mail with the list of these possible changes to Chris (and asking for support

for Susan because she had indicated in our telephone conversation that she was not in fact the final

decision-maker for ELA standards). A week later, I received a “Dear John” letter from Chris, thanking

me for my comments and indicating that my suggestions would be considered along with those from 50

states and that I would hear from the staff sometime in January.

In the second week of January 2010, a “confidential draft” was sent out to state departments of education

in advance of their submitting an application on January 19 for Race to the Top (RttT) funds. (About 18

state applications, including the Bay State’s, were prepared by professional grant writers chosen and paid

for by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—at roughly $250,000 each.) A few states included the

watermarked confidential draft in their application material and posted the whole application on their

department of education’s website (in some cases required by law), so this draft was no longer

confidential. It contained none of the kinds of revisions I had suggested in my December e-mail to

Minnich and Pimentel. Over the next six months, the Pioneer Institute published my analyses of that

January draft and succeeding drafts, including the final June 2 version. I repeatedly pointed out serious

flaws in the document, but at no time did the lead ELA standards writers communicate with me (despite

requests for a private discussion) or provide an explanation of the organizing categories for the standards

and their focus on skills, not literary/historical content.

One aspect of the ELA standards that remained untouchable despite the consistent criticisms I sent to the

standards writers, to those in charge of the VC, to the Massachusetts board of education, to the

Massachusetts commissioner of education, to the media, and to the public at large was David Coleman’s

idea that nonfiction or informational texts should occupy at least half of the readings in every English

4

class, to the detriment of classic literature and of literary study more broadly speaking. Even though all

the historical and empirical evidence weighed against this concept (and there was none supporting it), his

idea was apparently set in stone.

The deadline for producing a good draft of the college-readiness and grade-level ELA (and mathematics)

standards was before January 19, 2010, the date the U.S. Department of Education had set for state

applications to indicate a commitment to adopting the standards to qualify for Race to the Top grants. But

the draft sent to state departments of education in early January was so poorly written and contentdeficient

that CCSSI had to delay releasing a public comment draft until March. The language in the

March version had been cleaned up somewhat, but the draft was not much better in organization or

substance – the result of unqualified drafters working with undue haste and untouchable premises.

None of the public feedback to the March draft has ever been made available. The final version released

in June 2010 contained most of the problems apparent in the first draft: lack of rigor (especially in the

secondary standards), minimal content, lack of international benchmarking, lack of research support.

In February 2010, I and presumably all other members of the VC received a “letter of certification” from

the CCSSI staff for signing off on Common Core’s standards (even though the public comment draft

wasn’t released until March 2010 and the final version wasn’t released until June 2010). The original

charge to the VC had been reduced in an unclear manner by unidentified individuals to just the first two

and least important of the three bullets mentioned above. Culmination of participation on the committee

was reduced to signing or not signing a letter by the end of May 2010 asserting that the standards2 were:

1. Reflective of the core knowledge and skills in ELA and mathematics that students need to be college- and careerready.

2. Appropriate in terms of their level of clarity and specificity.

3. Comparable to the expectations of other leading nations.

4. Informed by available research or evidence

5. The result of processes that reflect best practices for standards development.

6. A solid starting point for adoption of cross-state common core standards.

7. A sound basis for eventual development of standards-based assessments.

The VC members who signed the letter were listed in the brief official report on the VC (since committee

work was confidential, there was little the rapporteur could report), while the five members who did not

sign off were not listed as such, nor their reasons mentioned or letters shared. Stotsky’s letter explaining

why she could not sign off can be viewed here,3 and Milgram’s letter can be viewed here.4

This was the “transparent, state-led” process that resulted in the Common Core standards. The standards

were created by people who wanted a “Validation Committee” in name only. An invalid process,

endorsed by an invalid Validation Committee, resulted not surprisingly in invalid standards.

States need to reconsider their hasty decisions to adopt this pig in an academic poke for more than

substantive reasons. First, there has been no validation of Common Core’s standards by a legitimate

public process, nor any validation of its college-readiness level in either mathematics or English language

arts by the relevant higher education faculty in this country. State standards typically go out for a lengthy

and timely public comment period (not usually during the summer when teachers and administrators are

not in their schools) and for revision before approval by a board of education.

5

Second, boards of education generally have no statutory authority to decide on college-readiness levels

for credit-bearing post-secondary courses. This is the prerogative of a board of higher education or board

of regents or trustees. State legislators seeking to explore the legitimacy of the votes taken by their

boards of education in 2010 might request an investigation by the inspector general in their attorney

general’s office. Inspector generals are by statute allowed to determine whether the process followed by a

state agency, committee, or board in making a policy decision abided by statutory authority and followed

appropriate procedures.

Third, there is nothing in the history and membership of the VC to suggest that the public should place

confidence in the CCSSI or the U.S. Department of Education to convene committees of experts from the

relevant disciplines in higher education in this country and elsewhere to validate Common Core’s collegereadiness

level.

It is possible to consider the original vote by state boards of education to adopt Common Core’s standards

null and void, regardless of whether a state board of education now chooses to recall its earlier vote. Any

tests based on these invalid standards are also invalid, by definition.

1The lead ELA standards writers listed in 2009 were David Coleman, James Patterson, and Susan Pimentel.

2Keep in mind that the final version was not released until June 2, 2010 and many changes were made behind the

scenes to the public comment draft released in March 2010.

3http://nyceye.blogspot.com/2013/08/mass-standards-czar-stotskys-letter-on.html

4ftp://math.stanford.edu/pub/papers/milgram/final-report-for-validation-committee.pdf